The humidity was simply insane. Even when the sun was not yet high in the sky and the asphalt was still actually cool to the touch, the moisture in the air made everything you saw seem to be dancing in front of your eyes. For people who have never visited South East Asia, this is not a familiar thing to see. This is what 100 percent humidity looks like.

It was 1997 and I was back in Makassar, my hometown. I meet my wife while I was studying in U.S., so when it came time to tie the knot, we decided to have the ceremony in Indonesia. It would also be a great opportunity to introduce her to my parents for the first time.

It was a joyful moment to be able to see my family again after such a long absence. By that time, I had been out of the country for almost ten years. I initially went to the United States just to study. However, because my skill set was needed for the U.S. Government, I was able to apply and get accepted to become a permanent resident.

When I arrived at my childhood home, I felt weirdly familiar but distant at the same time. After being in United States for so long, I adopted it as my new home. The house I grew up in looked a lot smaller than I remembered. After only two knocks at the door, I heard footsteps of people coming running. It was my dad, my mom, and all of my brothers. I was shocked to see so many people all at one. They had been waiting for my arrival for hours. My dad and my mom, they looked older than I remembered. My brothers were still as funny and stupid as I remembered them. It didn't not take long for me to get back to memories of the old days.

After spending a long night catching up, the next morning I took a bike alone and started cruising around the town. My hometown had changed so much. I barely recognized the street that I grew up on. In just fifteen minutes of biking around the street and alleyways, I found myself lost and had no idea where I was. The large empty field where I used to play soccer was all gone now. In its place, there was a new six-story apartment building. The small fish market had been replaced with a huge modern mall, surrounded by office buildings. Big retail stores like Nike, and American fast food chains like Kentucky Fried Chicken and Burger King, had popped up on every corner. The economy was beating at a different rate than when I left. What had once been sleepy had rapidly accelerated to to a cappuccino-induced heartbeat.

The Indonesian economy had grown fast, making it part of the new Asia Tiger economy, and the envy of many Asian countries. Business was fueled by cheap loans and investments from developed countries, mostly Japan and the U.S.A. The loans came with low low interest rates, which pushed many business people toward absurd expansion.

This avalanche of liquidity blinded the government, and it became more greedy and corrupt as the days went by. Gone were the days of reasonable business; this was a go go era. Everything was a go.

Many new banks were created overnight. Banks especially bought into the idea that any assets would continue to go up in value. They went on borrowing sprees, leveraging their customer deposits and balance sheets as collateral. They pushed the economy until it overheated, and suddenly became vulnerable to any downturn. One single piece of economic bad news could tip the country into a downward spiral, like an out of control train on the wrong track.

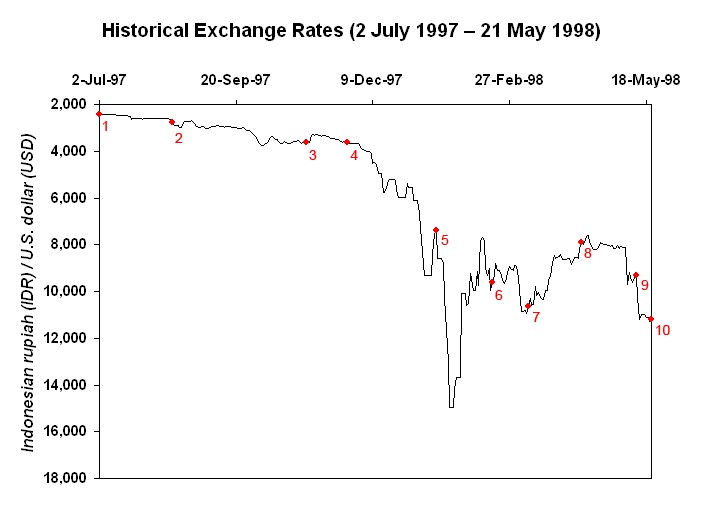

That is precisely what happened in late 1997, when George Soros, a billionaire U.S. hedge fund manager, predicted that there was something fundamentally wrong with the Indonesian economy. He ended up shorting the US dollar against the Indonesia currency, which sent Indonesia’s fragile economy into a tailspin in less than one month.

Investors started to flee with their capital and expose the corruption of the Indonesian government. Many banks started to close down, having lost tons of money. To stop the run on the banks, the government decided to devalue the currency. All cash became worthless. Overnight, the value of the Indonesian currency, the rupiah, plummeted 700 percent. Many families saw their savings wiped out. People started to take to the streets and protest the injustice, setting fire to cars and shops.

The government was lead by a ruthless general named Soeharto who, instead of calming down the country, went the other direction, using the military to suppress the popular uprising with tear gas and rubber bullets. The fight raged for weeks, with students and workers on one side and a highly trained militia on the other. It was not a fair fight.

I did not want to leave. I was worried about my family’s well being. I asked my dad what should I do, how could I help them get out of the chaos. He just looked at me quietly and with sadness, said this: "Just go my son, and save yourself. We will be OK.”

I knew he was just putting on a brave face, but I didn't have many options. I had a green card and my wife was already a U.S. citizen. Who knew how long the airport would be open in the midst of this crisis? For us, leaving was the right choice. I decided to cut my trip short, and head back to the United States the next day.

On the way to the airport, from the toll road, I could see flames billowing on the landscape from multiple building fires. Two weeks ago, this place was a paradise, but on the day I left, it looked like a war zone. The May Massacre had officially started.

The smell of burning tires is still present for me. The trauma is still here. Twenty years later, in 2020, I feel the same feelings of despair, anxiety, and hopelessness with America in the middle of the global pandemic. I feel like I am back in Indonesia, but this time I am actually in America. It is an unbelievable feeling. It is hard to comprehend.

Everyday, the news is depressingly bad. The conflicts and the stupidity of people. Discussions going nowhere. No leadership coming from the White House. People getting offended about petty, unnecessarily trivial stuff. From confederate flags to face masks, we argue and argue, while the virus spreads fast like a wild fire. There are more people dying now than there were in the Indonesia crisis.

When the first reported incidence of the virus struck the U.S., it happened in my home state of Washington. Information came slowly and was incomplete, but it mentioned that Covid-19 affected people who have problems with their immune system and breathing difficulties. My daughter has all of those risk factor. She was born with an autoimmune disorder, complicated further by Asthma. It is not a good combination for the virus. She had a work assignment to be in San Louis Obispo, a small college town in Southern California. While it was still not safe, as California was experiencing the same outbreak, San Louise Obispo had quite a low number of cases and sounded, at that time, like a better place for her.

While going to California would be better for her, she worried about us, and asked if it was ok to leave. I looked at her quietly and whispered, “Just go, my daughter, and stay healthy. We will be OK.”